Like many who have a complicated relationship to Orange is the New Black, I was eager to see what Season 3 would have in store for us. As a queer gal who likes a good 48 minutes of a trying-to-be-socially-aware dramedy that is full of lesbians and a decent soundtrack, I am a fan of the show. As a feminist critical media studies scholar and prison abolitionist activist, I haven taken issue with several elements of the show, both in terms of representation and also with the show’s creator, Jenji Kohan. Season 3 wasn’t perfect, but it did a lot of things right, and overall I thought it was strong. Here are some random and general reflections about some themes that caught my attention most.

(Obvi, major spoiler alert.)

On Starting with a Mother’s Day-themed Episode

The first episode of the season took place on Mother’s Day and provided us backstory on several of the inmates relationships to their mothers and/or children. It was impossible not to feel moved by these stories, and this theme also allowed the show to highlight the devastating reality of incarcerated mothers. According to a recent article published in the Columbia Social Work Review, nearly 75% of all incarcerated women were the primary, and sometimes sole, caretakers of children prior to their arrest. The impact of this is detrimental to both the mothers and the children, who most often end up in the foster system. There is also a heavy psychological toll that this separation creates on mothers and children; the same study states that children of incarcerated mothers are at high risk for long-term mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, isolation, and anger. This episode of Orange also provides us a moving depiction of the psychological and emotional turmoil experienced by the powerless mothers on the inside. In one of the final scenes, the father of Ruiz’s child tells her it’s the last time he’ll be bringing her daughter to visit because she’s getting old enough “to understand” that her mother is in prison. Ruiz breaks down, screaming in protest. Her daughter is carried away and she can do nothing about it. The plight of the incarcerated mother illustrates the dehumanization and denial of human rights experienced by all incarcerated people.

While the mother’s in the prison struggle, Pennsatucky decides to have a symbolic funeral for the three fetuses she aborted prior to her time at Litchfield. Boo approaches her to try to help ease her guilt and proceeds to give a speech in which she uses neoliberal wetdream Freakonomics as a defense of abortion. Boo explains: “They have this chapter in it, ‘Where have all the criminals gone?’ In the 1990s, crime fell spectacularly and this book attributes that to the passing of Roe V. Wade….The abortions that occurred after Roe v. Wade, these were children that weren’t wanted. Children who if their mothers had been forced to have them, would have grown up poor, neglected and abused — the three most important ingredients when one is making a felon. But they were never born. So 20 years later, when they would have been of prime crime age, they weren’t there.”

Boo concludes: “You were a meth-head white trash piece of shit and your children, if they had been born, would have been meth-head white trash pieces of shit. So by terminating those pregnancies you spared society the scourge of your offspring. I mean, when you think about it, it’s a…blessing.”

White Lady Feminist (WLF) social media exploded in response, lauding the speech as “powerful and eye opening” and what Vulture writer Brian Moylan deems as “politically profound.” I, (technically a white lady feminist, but not a WLF), was not so excited about the use of white dude pop economist Steven Levitt’s defense of abortion, as it is wildly similar to the defense of eugenics. Yeah, eugenics, you know, that thing where they wipe out the undesirables of society so the Aryan race can flourish without their resources being wasted away by poor people and people of color? Yeah, that’s what Boo is arguing for visa vi Levitt’s Moynihan-esque account of crime and African American births.

Pro-choice activists, we can and should do better than get excited about pop culture moments of abortion defense that rely on racism and classism, kay?

Anyway, since not all the inmates at Litchfield were mothers, we had people like Nicki keeping it real for us about kids:

On Ruby Snooze, I mean Rose

This season introduces the character of Stella, an Australian with a short-term prison sentence for a crime that is not revealed to viewers. According to a billion straight girls, Stella/Ruby Rose (the actress that portrays her) is HOT. Like #makesyougayHOT. There are some solid think pieces that describe my feelings on this phenomenon, but what I really want to say about Stella’s character is that she is BORING. Ruby Rose’s acting skills are not good enough to convince us of any remote chemistry between her and Piper, so the whole storyline falls flat.

(I mean, yeah, she’s a babe, but I’m still #teampoussey.)

On Prison Guard “Romance” (& a major TW for Episode 3)

There are several storylines on Orange that reveal the reality of the sexual, emotional, and physical abuse of inmates by prison guards. According to a report released Thursday by the Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Nearly half of all sexual assault accusations reported in U.S. correctional facilities in 2011 were aimed at prison guards or staff.” It’s also key to note that these are reported cases, and that the likelihood is high that more abuse occurs and goes unreported. Unlike pervasive narratives about prison being a dangerous place because of inmate-on-inmate violence, this study reveals that it is more common for inmates to be in danger from the staff.

I start out with those statistics to emphasize the reality of the power dynamics between inmates and guards. It is not an equal relationship; the staff members and administrators are in positions of institutional power over the prisoners. Consent is always already compromised when one person is in a position of power.

This season we were witness to four instances of egregious relationships between prisoner and staff: Daya and Bennett, Red and Healey, Pennsatucky and Coates, and Nicky and Lusheck. For the most part, the show used the storylines as an opportunity to reveal the exploitative and detrimental nature of these relationships. It couldn’t get more explicit than when Pennsatucky is brutally raped by Coates (after we learn, through a flashback, that this is not her first time being raped). (Also, side note: it should go without saying that I would give a major TW for this, Episode 3). Nicky and Luschek’s non-sexual, but still somewhat intimate business partner relationship leads to Nicky getting sent away to Maximum Security Prison. Healy begins to develop feelings for Red and makes clear that he would provide her favors, but only if she was sincere about her feelings for him (which she pretended to have, but appears ultimately to not).

And then there’s Daya and Bennett. This storyline has been challenging for me because I catch myself feeling really moved by their love. Consent may be compromised, but emotions don’t always fall neatly in line with analyses of power, and I think it would be misguided to deny that there are real feelings between these characters. And yet; there is no way that I could bring myself to root for their relationship, given how utterly fucked it is for a prison guard to engage in a relationship like that at all. After being moved to tears when Bennett proposes, I felt both like Orange manipulated my emotions and also just like a bad anti-prison feminist. Ultimately, Bennett decides to abandon Daya and the baby, while Daya is left powerless to do anything about it. This conclusion reveals the inevitable imbalance of power between the two of them, but also left me with a lump in my throat (my relationship to the Martha Wainwright song they play in the background when he drives away didn’t help).

I’m still struggling with how I feel about the representation of romantic and/or otherwise emotionally intimate relationships between staff and inmates. Is it important to shed light on the nuance of emotions, or is it dangerous to evoke sympathetic feelings for such unacceptable relationships?

On the Prison Industrial Complex

They actually said the words “Prison Industrial Complex” (PIC) this season, and spent the whole season demonstrating the impact of the process by which prisons are expanding rapidly due to the influence of privatization and other profit-driven entities. Put another way, the PIC creates a business out of prisons that functions best with more workers (inmates); as a result, prisons are bought by private corporations, utilized for cheap (slave) labor, and directly influence the rise of mass incarceration. Private companies now have an interest in getting more people in jail, and so they put their hand in lobbying for “tough on crime” bills that criminalize as many things as possible. Prior to this season, Orange never used that term on a show, but when Piper explains to Alex that she’s back in prison because of “the system,” Alex concedes, “I’m just a fly in the web of the prison industrial complex.”

Naming this is not insignificant. Like most media representations of social issues, Orange has fallen into the trap of representing a structural phenomenon as something that is a result of individual choices. For example, in Season 1, Piper states to her mother during a visit: “I am in here because I am no different from anybody else in here. I made bad choices.” I know Orange is trying to make clear how white people commit crimes too, but this idea—that Piper has just a big a shot of ending up in jail as working-class people and/or people of color—is inaccurate. People end up in prison, primarily, because of disproportionate policing, and because the prison industry wants more money. Fortunately, Orange is has come a long way from it being about “bad choices.”

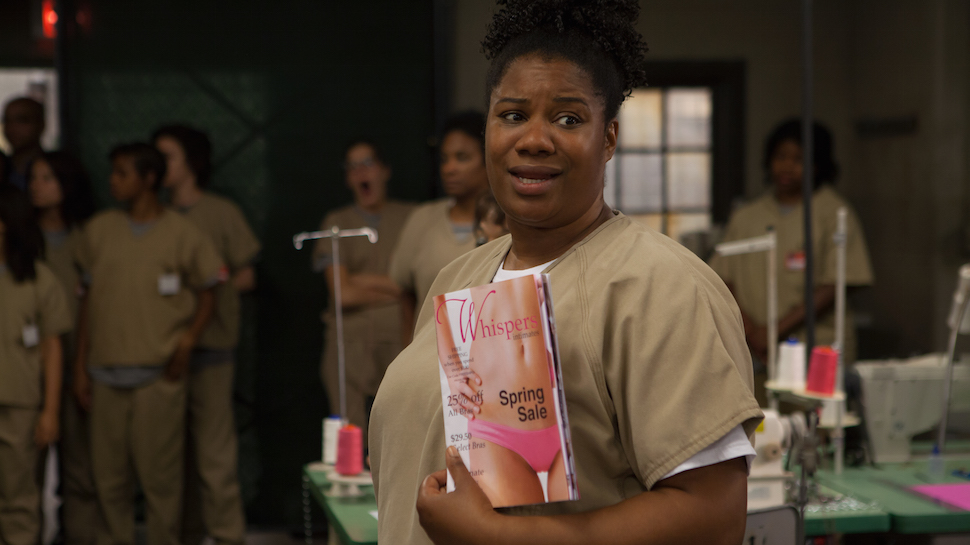

When Caputo finds out the prison is going to close, he takes matters into his own hands (via a homophobic blackmail exchange with Fig) and gets a private company, MCC, to buy the prison. He saves his job, ensures the women don’t have to be relocated, and protects the jobs of the staff. In exchange, we witness the horrors of privatization: corporate leadership that has absolutely no understanding of the prison, a refusal to engage in sufficient training of the newly hired guards, and a commitment to cost-cutting and profit-increase above anything else. This results in the introduction of a new job available to the prisoners: making panties for $1 that MCC will then sell and profit (wildly) from. In addition to exploitative prison labor, the buy out leads to standardizing of of pre-made and nearly inedible cafeteria food, the placement of Sofia in the SHU, and, as we see in the final scene of the finale, a huge increase in the prison population. Bunk beds and double the inmates, but the same level of resources and infrastructure. This is the reality of the PIC and Orange is doing a pretty solid job explaining how it’s completely fucked.

On Sophia (& another TW for transgender emotional and physical violence)

Laverne Cox’s presence on our screens has been incredibly important. Her fame has allowed the voice of a trans woman of color progressive activist to take up space in public consciousness. For the most part, Orange has worked to use Cox’s character, Sophia, to draw attention to the violence and oppression experienced by trans women of color in the US.

Up until this season, stories of Sophia’s struggle have been largely relegated to flashbacks, in which we see the discrimination and challenges she experienced before being incarcerated. This season, we bear witness to the transphobic violence she experiences inside the prison. After Sophia and Gloria’s sons become friends, each mother blames the other for their respective sons recent bout of reckless behavior. As Gloria’s personal struggle with her relationship to her son deepens, her anger toward Sophia grows, and vice versa.

Aleida encourages Gloria to use Sophia as a scapegoat, and does so using every possible transgender slur in the book; (in my opinion, the use of the word “tranny” became gratuitous). Tension begins to build when Gloria picks a fight with Sophia in the bathroom and ends up getting pushed into a wall in the scuffle. From there, Sophia is viewed as dangerous and aggressive by most of the other inmates, leaving her feeling isolated and under attack. In a horribly violent scene, Sophia is attacked and left bloodied, bruised, and stripped of her wig. In response? She’s sent to SHU.

This is not a unique case, either inside or outside of prison. Trans people often bear the burden of being punished for surviving. In addition to overwhelming statistics of the number of transgender inmates who end up in solitary, consider also the recent case of CeCe McDonald, the transgender woman who ended up in prison for defended herself from a violent transphobic and racist attack.

I appreciate what Orange does to draw attention to these realities, especially when it took it a step further to connect Sophia’s stint in the SHU as connected to the profit-desires of the corporate bosses of MMR.

On the Union, Les Mis, and Complicated Feelings

After MCC takes over Litichfield, the guards begin to talk about unionization. As a labor-centric (re: union-obsessed) Leftist, it was hard for me not to be excited by this storyline. AND THEN, when Caputo steps up (temporarily) to lead the charge, the guards erupt in, “Do You Hear the People Sing?” from FUCKING LES MISERABLES. I mean, way to tug at a pinko’s heartstrings, Orange.

But here’s the thing about prison guard unions. They are not like other unions. As I argue elsewhere, prison and police unions are negotiating to further entrench capitalist white supremacy, not fight against (like the labor movement ought to be doing). In The Toughest Beat: Politics, Punishment, and the Prison Officers Union in California, Joshua Page (2011) argues that the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA), the prison guard union of California, contributes to the societal stigma against prisoners by framing all convicts as “animals” and guards as victims. He explains:

the union contributes to popular prejudices about prisoners and promotes warehousing as the primary, if not sole, purpose of imprisonment. The ‘toughest beat’ would not be so tough (and the union’s insistence that officers are victims would not ring true) if prisons were filled [with] people who, in general, just want to ‘do their time’ and move on with their lives—rather than animalistic individuals programmed to cheat and harm others. The CCPOA’s strategy to enhance its officers’ professional image, status, and compensation depends on the public, press, and politicians believing that California prisoners are the ‘worst of the worst.’ (p. 72)

We can see similar things going on at Litchfield. Let’s look again, for example, at Luscheck’s easy ability to send Nicky to Max just by saying she was more likely to have drugs than he was; (“It’s her, she’s a fucking junky!” he yells, and almost immediately after, Nicky is hand-cuffed). The guard’s word was taken over the inmate’s word and it resulted in another inhumane displacement.

Point being: Communist musical anthems will never fail to bring a tear to my eye, but I don’t know if I’m on board with collectively empowering a workforce that bolsters the PIC.

On Spirituality

An ongoing theme throughout the entire season was the inmates’ yearnings for a spiritual practice. We witness a culty religion form around Norma; we get to see Black Cindy discover Judaism first as a ticket to better food, and then as a path to liberation; and we watch Pennsatucky and Boo rework Christianity. But we also saw stories of faith— success of and failures in—manifest more subtly.

I was really drawn to this storyline for a couple reasons, but maybe most prominently is because of my experience engaging in a spiritual practice with convicted criminals. I taught yoga (which is, when done holistically, a spiritual practice) to incarcerated young men in a jail in Minneapolis for a year. When I first started, I felt like an out-of-touch bougie white lady who was appropriating an Eastern practice and shoving it onto boys of color who would have no interest in it. That thought changed immediately when I saw how much the boys loved practicing. How breathing and stretching and engaging in moving meditation offered them refuge and healing.

I think it’s really easy for some on the anti-prison Left be dismissive of spiritual practices as a fundamental part of transformative justice. Although I respect entirely secular Leftists decision to understand “the struggle” as their higher power (or whatever), for me, I don’t think we can have the kind of queer feminist transformative justice revolution we want without acknowledging a very spiritual sentiment: that the core of all sentient beings is love and humanity. That little aside is to say that not only does it make perfect sense to me that inmates are hungry to find God/gods/g-d/etc., but that this desire is a really important thing for us to consider when organizing to improve the lives of prisoners.

We learned some valuable lessons about faith and spirituality this seasons: Faith will fail us in the face of the systems of oppression. But it will also find us again and again and again, in smaller ways, so that we can keep surviving those systems. Arthur Chu from The Daily Beast said it better than me, so I’ll close this section with his words:

“Orange Is the New Black is a show about how Big Faith…is a trap—the kind of faith that believes in ultimate justice and in final answers, the kind that says you can be confident in how the story ends. It’s the kind of faith that’s brittle, fragile, that sets you up for a brutal fall. Orange Is the New Black is…a show that’s deeply skeptical that everything happens for a reason and everything works out in the end—as anyone who’s spent any time studying the real-life prison system would be.

But the other kind of faith? Little Faith? Faith as tiny as a mustard seed? The kind that won’t throw away the armor of cynicism but will take it off long enough for a swim, that says that there’s no clear path by which everyday kindness and love will fix this broken world and bring a happy ending to our story? That’s the kind of faith that, by not asking for too much, isn’t too easily broken. It’s the kind that can survive betrayal, suffering, hypocrisy—even prison.

It’s the kind that, behind bars or outside, you can’t live without.”

On that Beautiful Scene in the Lake

Speaking of faith….This gave me so much of it. It was a magic scene. My heart was full.

Bests and Worsts

*Best sex scene: Boo having sex with a former girlfriend; finally a lesbian sex scene with a strap-on! #beyondscissoring

Worst Sex Scene: Piper and Alex’s hate-fuck garbage bag romp. Also the worst, when the two characters identify empathy as a “boner killer” and suggest that having BDSM-style sex can only be a result of actual hatred toward another person. #smh

*Best one-liner: “Put ‘em inside her.” –Morello, with a shrug, after Suzanne asks what she should do with her hands during a hook-up with an admirer.

Worst one-liner: Piper’s diatribe about the vag sweat revolution. #eyeroll

(….that’s all I got right now, but please keep the list going in the comments :))

Additional reading

*Read this great piece for some important thoughts on the representation of the show’s only two Asian characters.

*Read this piece for thoughts on harmful portrayals of disability and benefits.

*Read this powerful interview with Laverne Cox about the themes addressed in Season 3 and how she coped with doing her job while performing something very triggering.

*Read this piece about what Orange gets right about depression.

***

What did you think of this season?